Paul McKeigue

- Summary

- Introduction

- Wiley’s biography

- Tsamota Limited and spinout companies

- Origins of CIJA: partnership between Tsamota and ARK

- CIJA’s working environment

- CIJA’s funding

- Investigation by the European Anti-Fraud Office

- Collaboration of CIJA investigators with armed opposition groups

- Evidence supplied by CIJA in court cases

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: ARK and other companies controlled by Alistair Harris

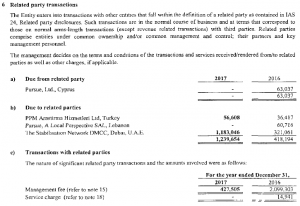

- Pursue Limited and Pursue a Local Perspective SAL

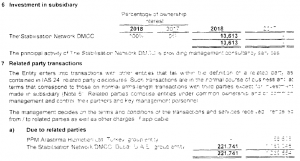

- Ark-Lebanon, ARK FZC and ARK Group DMCC

- The Stabilisation Network DMCC and The Stabilisation Network Limited

- PPM Arastirma Hizmetleri (PPM Research Services)

- Transactions between ARK Group DMCC and other companies controlled by Harris

- Hotch Potch Entertainment Ltd

- Appendix 2: the Koblenz trial

Summary

This note examines the role of the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) and other businesses controlled by William Harry Wiley in “transitional justice” related to the Syrian conflict, in the light of information that has become available through an investigation by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF).

- Wiley is a self-described “practitioner in the field of international criminal and humanitarian law” who has no legal qualifications other than a master’s degree. He has misleadingly described his PhD in military history as a thesis in “international humanitarian law”.

- CIJA originated in a covert UK-led strategic communication programme to support the Syrian opposition, as a spinout from two companies: ARK (founded by the presumed MI6 officer Alistair Harris) and Tsamota (founded by Peter Nicholson, a British military intelligence officer). Tsamota and CIJA are co-located and share the same director and key personnel. CIJA has received more than €37 million by mid-2020 from donors including governments of the UK, Canada, the US, and the European Union.

- Even larger scale funding from the FCO has been received by ARK and related companies including The Stabilisation Network and Pursue.

- Wiley has over the last ten years controlled at least ten companies in at least five jurisdictions, and is the sole director of most of these. Two legal entities with the name CIJA have existed: one is a Stichting (foundation) still registered in the Netherlands. The other was registered from 2014 to 2017 at an address found to be fictitious by OLAF investigators. Since 2016 Tsamota / CIJA’s physical location has been in Lisbon, though neither Tsamota nor CIJA are registered in Portugal as legal entitities. The OLAF investigators reported that “Tsamota has no stable structure and employs only consultants some of them with oral contracts”.

- Multiple irregularities have been identified in the activities of CIJA and Tsamota. In 2020 the EU’s Anti-Fraud office (OLAF) announced that that their investigation of CIJA, Tsamota and ARK “uncovers fraud”, and that there had been “submission of false documents, irregular invoicing, and profiteering” in EU-funded projects for which CIJA or Tsamota were contractors. OLAF made recommendations to “judicial authorities” (understood to mean recommendations for prosecution) in three countries.

- For one of these projects in Iraq, the EU had refused to pay the final invoice, leading to a court judgment in 2020 in which Tsamota was ordered to pay a further €378,855 euros plus legal costs.

- For another project involving Tsamota and ARK in Syria, OLAF recommended that the European Commission should recover €1.9 million of the €2 million originally awarded.

- Wiley’s posting to Baghdad in 2005-2008 where he worked for an office of the US Embassy (the Regime Crimes Liaison Unit) indicates that the US government was prepared to entrust him with sensitive tasks.

- Other key figures in CIJA include US State Department officials, a Saudi diplomat, and another British military intelligence officer. This has raised concerns that CIJA is under the covert influence of states that are belligerents in the Syrian conflict.

- CIJA’s ability to work with the most extreme armed opposition groups in the Syrian conflict to retrieve documents from opposition-held areas raises doubts about CIJA’s neutrality and commitment to human rights.

- Wide publicity has been given to CIJA’s possession of what has been described as the “linch-pin” of CIJA’s case against the Syrian government: a collection of documents recording the activity of the “Central Crisis Management Cell” (CCMC) established by the Syrian government in late March 2011. Close examination of these documents, deposited in a US federal court in 2018, shows that they are far from incriminating, and that the court deposition by CIJA’s analyst has distorted the content of these documents to make it appear that the Syrian government was responding to unarmed demonstrators with mass arrests.

- CIJA has since 2015 prepared reports on the “Caesar affair” – photographs of some 6000 deceased adult males taken up to August 2013 at Hospital 601, alleged to have been detained by Syrian security forces. This story has formed the basis for legislation for sanctions in the US Congress. From the evidence available, it is clear that the key witness is unreliable and it remains an open question as to which side perpetrated these atrocities.

- CIJA’s collaboration with international organizations allows it to feed evidence to investigations undertaken by these organizations. This includes the signing of a memorandum of understanding between CIJA and the UN International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) in 2017, tasked with investigating war crimes in Syria, followed by the signing of another agreement in 2018 between the IIIM and the OPCW allowing information-sharing with the Investigation and Identification Team, tasked with identifying the perpetrators of alleged chemical attacks.

- The funding of CIJA by donors has produced few indictments. It has been widely reported that CIJA provided evidence leading to the arrest in Germany of two former officers in the Syrian security service whose trial began in Koblenz in 2020. Both were were defectors who had left Syria in 2012. One of them had been debriefed by a western intelligence agency, and had been subsequently been a member of the opposition delegation to the Geneva conference in 2014.

- CIJA’s dissemination of a narrative of regime crimes has however contributed to delegitimizing the Syrian government and thus to laying the basis for sanctions and to the illegal US military occupation of Syrian territory.

Introduction

The targeting of civilians during the Yugoslav civil war led to calls for resolution of such conflicts to be accompanied by “transitional justice” and the formation of international tribunals to prosecute perpetrators. In the Syrian conflict, one of the most prominent organizations reported to be gathering evidence of crimes allegedly committed by the Syrian government is the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), established by William Harry Wiley, a Canadian former army officer.

Wiley’s biography

From a CV dated June 2008 on the website of the EU-funded Case Matrix Network, his LinkedIn profile and other publicly available sources, his biography can be reconstructed:

- 1963 November: born in Toronto

- 1982-1985: BA in Modern History at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario

- (dates not given): Master of Studies in Modern European History and Social and Political Thought, Oxford

- 1982-1997: “Active Duty and Reserve Service” in the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s Regiment), reaching rank of Captain by 1996.

- May 1996 – PhD at York University Toronto On the CV filed with Case Matrix Network the thesis title is given as War Crimes and the Evolution of International Humanitarian Law. On the CIJA website this is described as a “PhD in international humanitarian law” and in a puff piece for the Toronto Globe and Mail in July 2019 as a “PhD in international criminal law”.

- March 1997 – September 1999: Analyst, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Section, Department of Justice of Canada, Ottawa.

- (dates not given): LLM (master’s degree) in International Public Law at Leiden University, Netherlands

- May 2000 – March 2001: Intelligence Analyst, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, The Hague, Netherlands

- March 2001 – March 2002: Investigator, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda

- March 2002 – October 2003: Intelligence Analyst, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, The Hague, Netherlands

- October 2003 – September 2005: Investigating Attorney, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, The Hague, Netherlands

- September 2005 – March 2008: posted to Baghdad. His CV describes this posting as:

- September 2005 – March 2006: Human Rights Officer, United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq, Baghdad, Iraq.

- April 2006 – March 2008: International Law Adviser, Defence Office, Iraqi High Tribunal.

- December 2009: Director, Tsamota Limited (a consultancy advising the mining industry)

- 2011: Tsamota partnered with ARK to set up SCJA, later renamed CIJA

Inconsistencies and misrepresentation

Lack of legal qualifications

Wiley’s carefully-worded description of himself as “a practitioner in the field of international criminal and humanitarian law”, has been widely taken to mean that he is a lawyer, for instance in the film Saving Saddam. However Wiley has no visible legal qualification other than a one-year master’s degree in Public International Law. Despite this his CV gives his job title from 2003 to 2005 as “Investigating Attorney”. His job titles from 1997 to 2003 were “Analyst”, “Intelligence Analyst”, or “Investigator”. In November 2016, Wiley gave evidence to the Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Canadian House of Commons. After he had been introduced by the Chair as a “Canadian lawyer”, he reintroduced himself with “I would reiterate that my name is indeed Bill Wiley. I am the executive director of the CIJA.” but did nothing to correct the Chair’s description of him as a “Canadian lawyer”. He did not correct this until he spoke at an online event at King’s College London on 24 February 2021, by which time he had seen a draft of this briefing note.

Theme of PhD thesis

The title of Wiley’s PhD thesis was “Onward to New Deeds!” The German Field Army and War Crimes during the Second World War, submitted from the Department of History at York University Toronto where his supervisor was the distinguished historian Professor Michael Hans Kater. The theme of the thesis – that the massacres of civilians by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for real or imagined actions by irregular combatants were part of the doctrine of the Prussian and later the German army – is widely accepted. Whatever its academic merit, it is a stretch to describe it as a thesis on “the evolution of international humanitarian law”.

Dates of service in the Canadian Army

Wiley’s LinkedIn profile gives the end of his army service as 1997; he does not appear in social media postings related to the regiment after 1996. His CaseMatrix CV however gives the end of his service as 2002 and lists the period September 1999 – May 2000 as “Active Duty”.

Affiliation to the US Embassy during his posting to Baghdad

Other accounts state that at least from April 2006 Wiley was working for the Regime Crimes Liaison Office (RCLU), described by the US Justice Department as “an independent office of the US Embassy in Baghdad”, established in May 2004 as the lead US government agency for support to the Iraqi Special Tribunal (IST) constituted to hear cases against senior Iraqi officials. Neither of Wiley’s published CVs mention his affiliation to the RCLU: he describes his post in 2006-2008 as “International Law Adviser, Iraqi High Crimes Tribunal”. Lawyers who were on Saddam Hussein’s defence team tell us that Wiley “was in full control of the Tribunal, so much so that no lawyer could have submitted a document to the Tribunal without [Wiley’s] prior approval”.

Tsamota Limited and spinout companies

Tsamota Limited was originally registered in 2006 at a London address by Peter Richard Nicholson who was then working for the international criminal tribunals in The Hague, having in August 1994 reached the rank of Major in the British Army’s Intelligence Corps. By 1998 he was still listed as a Major in the Intelligence Corps but had transferred to the reserves (Territorial Army) in which capacity he was awarded an Efficiency Decoraton. Nicholson’s CV records that in 2015-16 he worked for CIJA “investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity in Syria and Iraq for EU governments.”

The filing history at Companies House shows “Accounts for a dormant company” for the first three years, but the linked documents show that the company was trading. In December 2009 Wiley became a director. In 2013 the registered office was moved to Lancashire and all the shares were transferred to Wiley, now sole director. This appears to coincide with the start of EU funding for Tsamota, described later. The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) reported that in an unannounced visit to this address in September 2015 “no one was found at the premises”.

The Offshore Leaks database hosted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, based on the Paradise Papers, lists William Harry Wiley as sole director, shareholder and judicial representative of a company named “Tsamota Group Ltd” (company number C63303) registered in Malta on 27 December 2013. Two employees of a Maltese law firm Mamo TCV are listed as “secretary”. The current status of this company is listed as “in dissolution”.

The balance sheet of Tsamota Limited at end of 2019 showed current assets of £777,326 and current liabilities of £1,239,372. On LinkedIn the company’s services are described as:

We offer bespoke consultancy services built around the ethical provision of specialised advice and the undertaking of operational as well as strategic tasks in support of companies, governmental agencies, IGOs, NGOs and individuals. Broadly speaking, Tsamota works in the fields of justice- and security-sector reform, principally in conflict and high-unstable security environments, for instance, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

As reported, by Max Blumenthal and Ben Norton, a core component of Tsamota’s business model was advising companies in the resource extraction sector on how to mitigate the risk of prosecution for human rights abuses when operating in unstable environments. A presentation given by Wiley in 2013 on “Individual Criminal Responsibility and Mining Companies” gives a hypothetical example of a scenario in which such risks might arise:

- MineCo operates a mine in South Africa.

- A wildcat strike erupts and MineCo calls in Secure Corp (a private security firm) to manage labour unrest

- In the course of re-establishing order, armed Secure Corp employees shoot and kill 8 MineCo workers

The presentation lists the solutions offered as: “Security and Human Rights Assurance, Security and Human Rights Training and”Investigations of Alleged Human Rights Abuses and Security Force Violations”.

A similar presentation was given by Adrian Powell as Chief of Staff of Tsamota Ltd in 2015

In 2014 and 2015 Wiley created four other companies, all registered at the same address in Bury, Lancashire:

- TSAMOTA NATURAL RESOURCES LIMITED (09610148)

- TSAMOTA GROUP LIMITED (09608115)

- TSAMOTA CRIMINAL EVIDENCE SOLUTIONS LIMITED (09461746)

- TSAMOTA CERTIFICATION LIMITED (09134802)

In March 2018 Tsamota Certification Limited brought a case in the US District Court of Wisconsin against ANSI ASQ National Accreditation Board for breach of contract and unjust enrichment. The action was dismissed with prejudice in April 2018. The judgement included a concise explanation of Tsamota Certification Limited’s business model:

Plaintiff is in the business of providing auditing and certification services to private security companies (“PSCs”). This service, known as Private Security Company Management Services (“PSCMS”), has grown over the past fifteen years with the increased use of PSCs by governments and because of various well-publicized incidents of human rights abuses perpetrated by PSC personnel.

Origins of CIJA: partnership between Tsamota and ARK

CIJA, like the companies named Mayday Rescue set up by the late James Le Mesurier to channel government support for the White Helmets, was spun out of a company named ARK FZC (later renamed ARK Group DMCC) registered in Dubai by the “former UK diplomat” Alistair Harris.

Alistair Harris’s biography

- 1973 – year of birth

- 1996-2002 – FCO diplomat

- Served in the Balkans, Central Europe and Pakistan.

- 2002-2005 – War Crimes Investigator, FCO and UN International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia

- 2006-2007,Consultant, British Embassy Beirut: Deployed Civilian Expert with the Post-Conflict Reconstruction Unit

- 2007-2013 Founder/director, Pursue Ltd, Lebanon and Yemen

- 2009- Founder/director, ARK Lebanon,

- 2011- Founder/director, ARK FZC (renamed ARK Group DMCC in 2015)

- 2014- Founder/director, The Stabilisation Network DMCC

- 2020 December – UK government Stabilisation Unit

Harris’s bio on the ARK Group DMCC site does not mention his career as a diplomat but describes him as “having spent 20 years working in conflict zones from Northern Ireland and the Balkans to Afghanistan, the West Bank and Lebanon”. This suggests that his real affiliation was with MI6, as a “UK diplomat” would not otherwise have been deployed to Northern Ireland. Harris’s companies and the transactions between them are described in detail in the Appendix.

The activities of Harris’s ARK Group in the Syrian conflict and in Lebanon are described in detail in batches of leaked FCO documents that appeared online in September 2020 labelled as Operation HMG Trojan Horse.

After the release on 11 December 2020 of documents describing in detail ARK’s role in Lebanon, Harris relocated to London, announcing on his LinkedIn profile that on 21 December 2020 he had been appointed to a new post with the Stabilisation Unit’s Civilian Stabilisation Unit.

A report to the FCO from ARK with title “UK FCO – STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS; RESEARCH, MONITORING AND EVALUATION SERVICES; AND OPERATIONAL SUPPORT IN THE SYRIA REGION” (TrojanHorse Ark 2.1.8.pdf) describes how CIJA was spun out from Alistair Harris’s company ARK and Wiley’s company Tsamota:

In 2011, in response to allegations of gross human rights violations committed by protagonists in the Syrian conflict, ARK and its justice sector partner Tsamota supported the establishment of the Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability (SCJA). The SCJA has grown to be a majority-Syrian not-for-profit organisation with over 90 staff committed to ending impunity for crimes carried out by all armed factions in Syria. Initially working with seed funding from the UK Conflict Pool to support investigative and forensic training for Syrian war crimes investigators, the project experienced several stages of sustainable growth. It secured funding from the US-supported Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) to extract contemporaneous documentation from the conflict zone, and in May 2012 obtained funding from the EU Instrument for Stability to support the development of its analytical and headquarters components. With a deployed in-country field team and trained investigators supporting documentation collection, exfiltration, archiving and analysis, the SCJA has grown to become a major component of Syria’s transitional justice architecture. By August 2014, when the EU component of the project ended, ARK and Tsamota were able, as planned, to step away from the day-to-day operations of the SCJA, which is now firmly established as a coherent, independent, Syrian organisation. To date the project has collected over 1,500kgs of contemporaneous documentation from inside Syria, scanned or is in the process of scanning over 310,000 pages of evidential material as well as reviewing and indexing over 12,000 videos, all of which had to be hand carried from Syria. This project marks a new development in international justice: the contemporaneous gathering of evidence of violations of international humanitarian law, whether conducted by regime forces or members of armed opposition or Islamist groups, whilst the conflict is ongoing. In addition to harnessing complementary funding streams (UK for in-country investigative capacity, US for documentation and archiving and EU for analysis and support) ARK and Tsamota were able, through a donor government project steering committee, to further expand the funding base. By September 2014, the project had secured Norwegian, Swiss, German and Danish funding, achieving sustainability, and realising core objectives.

A slightly different account is given in another document with title “AJACS Technical Proposal ARK FZC” (TrojanHorse 2.1.5 [4].pdf):

ARK is able to draw on transitional justice expertise from the independent Syrian NGO, the Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability (SCJA). The SCJA was established in The Hague in November 2011 with direct technical assistance from ARK.

The SCJA first appeared online in September 2012 with four training videos on documenting evidence of human rights abuses, posted on a YouTube channel. CIJA’s letter to donors in May 2020 stated that SCJA was established in May 2012 and registered in the Commercial Registry in the Netherlands in November 2012. “Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability” was the name of the recipient of the first tranche of FCO funding in November 2013. An article published in December 2012 described SCJA as “a non-profit organization based in The Hague but operating mainly in Istanbul”.

A guide to “documentation groups” in Syria posted by Public Law and International Policy Group in March 2013 described the relationship between SCJA and ARK as follows, quoting ARK’s website:

ARK has been working with implementing partner Tsamota Ltd. (see below) to provide pro bono training and support for investigators selected by the Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability (SCJA) (see above) since May 2011. Together, these organizations have provided direct assistance to the UNHRC Commission of Inquiry (see above), which has acknowledged their TJE collection efforts.

The first component of ARK’s and Tsamota’s program involved training Syrian investigators in basic international criminal and humanitarian law. Specifically, trainings focused on the links between international humanitarian law and human rights law, as well as possibilities for a domestic justice process in a future transitional Syria. Simultaneously, ARK and Tsamota provided training on international criminal investigative methodology.

This partnership between Tsamota and ARK in 2013 appears to be the EU-funded Rule of Law project in Syria that was investigated by the European Anti-Fraud Office as described below.

Other key personnel associated with CIJA

Nerma Jelačić

Jelačić is now Director of External Relations, having joined CIJA in October 2014. She had worked as a journalist after graduation in London in 1999, and subsequently as head of communications for the ICTY Hague tribunal. Since 2016 she has been one of the three directors of the Stichting (see below).

Stephen Rapp

Stephen Rapp, a former US foreign service official, is reported to chair the CIJA. From 2009 to 2015 he served as the United States Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues. In 2005 he was Chief Investigator for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, supervising a team of investigators whose key witness, the Rwandan politician Juvénal Uwilingiyimana, was murdered in Brussels. The crime was never solved, and it was never established whether a letter allegedly written by the victim, complaining that the investigators were attempting to coerce him into giving false testimony, was authentic or fake.

“Now we have 800,000 pages of original documents, signed and sealed with original signatures going all the way up to Assad that document this whole strategy,” Ambassador Stephen Rapp told Pelley. Rapp is a former U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues in the Office of Global Criminal Justice. He believes that the documents and photographs taken of the atrocities committed by the Assad regime create a trove of some of the strongest evidence ever seen in war crimes tribunals. We see reports back about ‘well, we’ve got a real problem here, there are too many corpses stacking up, somebody’s gonna have to help us with that,’ Rapp explained.

No documents so far made public include any report that bodies of people detained by security forces were “stacking up”, although by November 2011 the CCMC recorded that security forces were finding bodies of unidentified civilians killed by the opposition.

Christopher Engels

Engels described his position as Director of Investigations and Director of Operations at CIJA. Since 2016 he has been one of three directors of the Stichting. Like several others he has connections with the Balkans: at a hearing of the US Helsinki Commission in 2016 an outline of his biography was given:

His past posts include head of section for the Justice Sector Support Project Afghanistan, director of the criminal defense section of the Court of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and acting deputy head of the defense section at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. He was recently head of rule of law for the OSCE Mission in Bosnia, and worked in the office of the legal advisor of the US Mission in Kosovo.

He graduated from Mississippi College with a degree in sociology in 2000, and was employed as a “consultant in the legal department” with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Vienna before he had even started law school. He was admitted to the Mississippi Bar in October 2004. His post as the Director of the Criminal Defence Section of the War Crimes Chamber of Sarajevo was around 2007, when he addressed the Assembly of States Parties of the ICC in New York, In 2011 he was regional coordinator of the EU-funded War Crimes Justice Project.

In at least two of the posts listed above, he would have been working for the US State Deparment. The Justice Sector Support Program began in 2005 as an initiative of the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs of the US State Department. The US Mission in Kosovo was known as the US office in Pristina until it became the US Embassy in 2008.

America’s leadership has promoted international justice from its earliest days. We were the engine behind the Nuremburg Tribunal and the other post-WWII prosecutions. We were a driving force for the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals. America has been an advocate of justice across the world and ready to stand up against dictators who were killing their people.

Adrian Powell

Adrian Martin Powell a former military policeman in the UK who subsequently trained as a solicitor, was the chief of staff of CIJA from 2013 to 2015. On the website of his current partnership he records that:

from 2006 to 2013 he spent the majority of his time in Iraq and Afghanistan as a legal advisor with various entities including the US DoD, a major private security company and the UK FCO. From 2013 to 2015 he managed a significant legal project focusing on war crimes in Syria. As our senior legal partner he brings expertise in the legal complexities and geo-politics faced by our clients. Adrian is security cleared to a high government standard.

Ewan Brown

Ewan McGregor Brown is a Senior Analyst at CIJA. A summary of Ewan Brown’s CV is available from a record of a decision in 2010 at what was then the “International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991.”

Ewan Brown has a degree in Modern History as well as a masters degree in Criminology. He was employed from 1986 to 1996 as British Army Intelligence Officer “working at various levels of military command, including active service in Northern Ireland, Middle East and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ewan Brown”trained and gained experience in the direction, collection, analysis and dissemination of military information and intelligence product”.

The London Gazette records his commission in January 1986 as 2nd Lieutenant on probation in the Royal Corps of Transport, but there are no subsequent records of promotion, transfer to reserves, or discharge from the Army. In an earlier briefing note on the Integrity Initiative, we determined that some officers in the Intelligence Corps work under civilian cover. In a court case in the US where he gave evidence, Brown described himself as a “consulting analyst and investigator, and former British Army officer” but did not mention his role as an intelligence officer.

Board of Commissioners

There is a four-man “Board of Commissioners” consisting of Stephen Rapp, Larry D Johnson (another US national who served as Chief of Cabinet of the ICTY), Alex Whiting (a former US federal prosecutor) and Nawaf Obaid.

- Nawaf Obaid was a Saudi diplomat from 2003, based in the London embassy from 2012 to 2016. His other job is as CEO of the Essam and Dalal Obaid Foundation, where the other board members are his brothers Karim and Tarek Obaid (cofounder and CEO of PetroSaudi) and Dalal Obaid.

- Toby Cadman In a submission to the International Criminal Court dated 23 January 2020 requesting “Leave to Submit Amicus Curiae Observations” the lawyer Toby Cadman of Guernica 37 International Justice Chambers states that he serves on the board of CIJA and that he

further offers specialist political and public affairs consultancy services advising clients how best to identify, approach and influence the key decision makers of Westminster, Washington DC, Brussels and further afield.

Other members of Guernica 37 include Mazen Darwish whose NGO recently submitted a criminal complaint concerning alleged chemical attacks in Syria to the German federal public prosecutor in Karlsruhe, and Emma Le Mesurier who joined as a Fellow in November 2020. On 27 October 2020 Cadman quoted a tweet from Eliot Higgins endorsing the view that “disinformation promoted by Russia” had caused the death of James Le Mesurier with the comment that “It’s now time to start looking into their role and holding them accountable.”

As co-founder of a consultancy named the International Forum for Democracy and Human Rights, Cadman was hired in 2012 by the UK Foreign Office to “head a team to investigate crimes committed in the Syrian Arab Republic“. Cadman’s work with Wiley dates back to 2015, according to Garance Le Caisne’s book Operation Caesar: At the Heart of the Syrian Death Machine:

In spring 2015 the CIJA agreed to an exchange of data with the lawyers working on the Caesar affair. William Wiley and the international lawyer Toby Cadman would work together on this. Cadman was, at that time, a member of the 9 Bedford Row International Chambers in London, which had picked up the baton from Carter-Ruck and Co, the authors of the report commissioned by Qatar.

On 3 June 2016 Cadman posted an article on the Huffington Post site announcing that he had joined a “non-profit group that brings together doctors, military and humanitarian specialists and lawyers” named Medics Under Fire, set up by Hamish de Bretton-Gordon (HdBG). We have reported previously on HdBG’s covert work in 2013 and his subsequent role, as founder of the CBRN Task Force, in providing fabricated evidence of a chlorine attack in the Syrian town of Talmenes to the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in 2014. Later that year the name was changed to Doctors Under Fire by HdBG, who posted a brief announcement on LinkedIn in November 2016:

Dr David Nott, Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, Dr Salayeh Ahsan and Toby Cadman have set up a new charity DoctorsUnderFire to protect doctors and medics in warzones

An article posted on 22 February 2018 noted that

The Charity Commission has no record of it [Doctors Under Fire], nor of ‘Medics under Fire’ which is what the Doctors Under Fire website is called.

Cadman did not reply to questions about his work with CIJA or his work with HdBG.

Fergal Gaynor

Fergal Gaynor, an Irish barrister who was shortlisted for Chief Prosecutor of the ICC, records on his LinkedIn profile and his online CV that he was Head of the Syrian Regime Team from 2017 to 2019. In this capacity he:

Oversaw the preparation of a 350-page brief articulating the criminal responsibility for senior members of Syria’s Military Intelligence Department for crimes against detainees, including the murder of the over 8000 detainees whose corpses were photographed by military police

This evidently refers to the Caesar photos, discussed below.

CIJA’s working environment

CIJA insiders report to us that the organization is run by an inner core consisting of Wiley and a few associates. In a speech in Florence in October 2017, Wiley described how the other staff are managed (quoted passages at 17:50 and 19:34):

Whilst we are an an NGO and I never thought in a million years I’d ever run an NGO given my professional background, but I think it’s fair to say that we differ from most or any other human rights NGO in that there is real discipline in CIJA. There is no thought police but people are expected to buy into the objectives of the organization, and where people buy into the objectives of the organization we know they’ve bought in because they’re gonna work hard and work well, and seek constantly to develop themselves professionally. Where we don’t see that kind of performance they’re gone. There’s no staff council, there’s no appeal. You can try to sue us, but we have a General Counsel and the contracts are so tightly done that you’re just wasting your money. So there is a certain ruthless streak, maybe this goes into the power …

So discipline, flexible hiring and removal options are very very very key, and having the courage – it’s rare in our institutions – to get rid of people. It’s another fundamental problem is the public institutions are utterly filled with dead wood – people who are a complete and utter waste of space …

In an online seminar at King’s College London, Wiley described a more empathetic style of leadership with staff who have a background in military or security services, noting how this field “’attracts a certain type” of adventurers who sometimes exhibit “crankiness”.

Netherlands location (2012)

Stichting The Commission for International Justice and Accountability (2012)

Stichting “The Commission for International Justice and Accountability”, was registered (KvK number 56509839) at the same address in The Hague as Stichting SJAC (KvK number 59036699) on 28 May 2012. The organization was originally registered as Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability: it was then an association, not a Stichting. On 1 November 2014 the name was changed to “The Commission for International Justice and Accountability” and on 30 May 2015 it became a foundation, with a legal name that included the word “Stichting. The directors since 16 June 2016 have been Wiley, Engels and Jelacic. A Stichting in the Netherlands is required to disclose very little information unless it has charitable (ANBI) status or its annual turnover exceeds 6 million euros for two consecutive years. This Stichting does not have ANBI status. It is registered with the US government System for Award Management as STICHTING COMMISSION INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE (DUNS #490856146), and is listed as an implementing partner in a strategic communication program funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund:

The Resonant Voices Initiative in the EU (RVI EU) is an online campaign intended to counter the radicalization and polarization among the Western Balkans diaspora communities living in the European Union.

The RVI EU is implemented by the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), and Propulsion Fund (PF), as part of the Civil Society Empowerment Program under the EU Internet Forum, with funding from the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police.

An advertisement in June 2019 seeks a short-term communications consultancy on the RVI EU, and mentions that the data controller is Stichting “The Commission for International Justice and Accountability”. The advertisement gives the email domain as cijaus.org

CIJA Support Services BV (2020)

This company was registered by Wiley on 3 September 2020 (KvK 80216307) at the same address as the Stichting (Laan van Meerdervoort 70).

Belgian location (2013-2015)

CIJA insiders have informed us that Tsamota and CIJA are co-located, sharing not only their director but other key personnel. CIJA was based in central Brussels until 2016. In 2015 Adrian Powell was Chief of Staff of both Tsamota Limited and CIJA. The devex website gives the location of the headquarters of Tsamota Ltd as Brussels, employing two people, with a contact email for Wiley as the primary contact, including a Belgian phone number. It lists five contract awards to Tsamota Ltd, four from the UN and one from the EU. A LinkedIn profile for Oliver Cushing states that he was employed in Brussels by Tsamota Ltd from 2013 to 2015 and as CEO of Tsamota Certification Limited from 2015 to 2016. An advertisement in November 2015 for an internship with Tsamota Certification Limited also stated that the location was Belgium.

In 2014 two nonprofit organizations were registered by Wiley at Molièrelaan 59, 1190 Vorst, Brussels. The legal term for a non-profit organization in Belgium is VZW in Flemish and ASBL (Association sans but lucratif) in French.

Tsamota Good Governance Foundation VZW (2014)

The only company with “Tsamota” in its name on the Belgian business register is The Tsamota Good Governance Foundation VZW (business number 0543.848.514) registered on 7 January 2014. The Tsamota Good Governance Foundation is listed on a US government database of award recipients with William Wiley as the contact name. At registration the directors were Wiley and Petronella Aleida van Laar who represented Tsamota at a UN forum on business and human rights in 2013 and later went to work for the UN as an investigator. On 2 Dec 2014 van Laar was replaced by Adrian Powell, then the chief of staff of both Tsamota and CIJA. On 6 July 2015 Powell was replaced by Nerma Jelačić.

The Commission for International Justice and Accountability (Belgium, 2014-2017)

The Commission for International Justice and Accountability (company number 0548.717.617) was registered on 19 March 2014 as an ASBL. The sole director at registration was Wiley. The registration mentions that the legal name in the Netherlands since 5 August 2014 was CIJA. The ASBL was liquidated on 30 September 2017.

No annual accounts have been filed for The Tsamota Good Governance Foundation VZW or The Commission for International Justice and Accountability ASBL, though this is a legal requirement for a non-profit association in Belgium. Molièrelaan 59 is a residential block with four apartments (based on the number of door buttons). In 2015 OLAF investigators found that this address was no longer in use, although at that time both these nonprofit organizations were registered there. A visitor has reported to us that this was Wiley’s home address until 2015, and that mail for Tsamota and CIJA continued to arrive after he had left, to be thrown in the bin by the new occupants.

Lisbon location (2016)

In 2015 several months after a visit to the Brussels office by investigators from the European Anti-Fraud Office, Tsamota / CIJA relocated to Lisbon. Although press reports refer only to a city in western Europe, it is widely known in ICC circles that the city is Lisbon. This can be documented in open sources. A job advertisement was placed by Tsamota Ltd in April 2016, seeking a Business Development Consultant based in Lisbon. Under the heading “Organisation Profile” the advertisement states “Tsamota Ltd. is a limited liability company specialising in the delivery of justice- and security-sector reform initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected environments.” At the bottom, under “How to apply”, applicants are advised to send “a letter of motivation, stating”why you wish to work with the CIJA” to an email address at the domain cijaonline.org. There is no other mention of CIJA in the advertisement. A CIJA representative attended meetings with the Portuguese government in January 2017 when the EU terrorism coordinator was in Lisbon. Nawaf Obaid’s LinkedIn profile gives Lisbon as the location for his post as Commissioner. A US government database of applicants for funding lists The Tsamota Good Governance foundation ASBL with Wiley as the contact name at its registered address in Brussels, but with a Lisbon (+351 21 prefix) phone number. No business named CIJA can be found in the Portuguese business directory.

CIJA’s funding

Engels stated in 2018 that:

Our current donors include the United Kingdom, Canada, the European Union, Germany, Demark, the Netherlands, and Norway. In a letter to donors written in May 2020, Wiley stated that “CIJA has thus far received fifty-nine grants from eleven donors, including five from the European Union. The total value of these grants is EUR 37.5m.”

From the email correspondence with donors in May and June 2020, it appears that another donor was the Open Society Foundation. For at least some of the EU and Canadian government funding that was awarded, the recipient entity can be documented to be the Stichting in the Netherlands. A grant of €1.5 million from the European Union to “the Commission for International Justice and Accountability” for 2016 to 2020 is listed as a grant under the “Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace” programme. The EU has confirmed, in response to an Access to Documents request, that this contract was signed with “the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA)”, Laan van Meerdervoort 70, 2517 AN, Den Haag“. This is the address of”Stichting The Commission for International Justice and Accountability“. A separate payment of €926,990 from the EU’s”Internal Security Fund – Police” to “Stichting The Commission for International Justice and Accountability” is listed as a grant agreement signed during 2018.

The Canadian foreign ministry (Global Affairs Canada) lists a grant of Canadian $1.5 million from 2018 to 2020 to “The Commission for International Justice and Accountability” and states that “This brings Canada’s total contribution to CIJA’s work in Iraq and Syria to $7.5 million.”

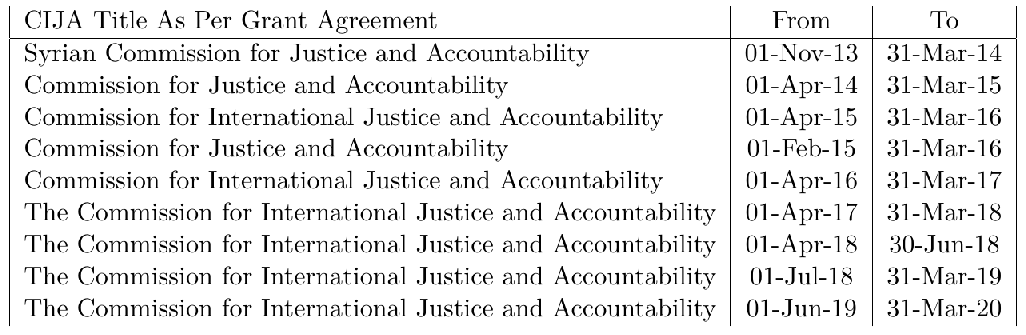

A letter from the FCO in response to Freedom of Information Act Request 2020/00016, dated 21 January 2020, listed the following grants to CIJA from 2013 up to that date.

The change of the name of the entity in the grant agreement from “Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability” to “Commission for Justice and Accountability” on 1 April 2014 is consistent with payments from this time onwards being made to the Belgian nonprofit that had been registered on 19 March 2014 at Wiley’s Molierelaan address (liquidated in 2017). The association registered in the Netherlands did not change its name from “Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability” to “The Commission for International Justice and Accountability” until November 2014. A Stichting must include the word Stichting in its legal name. The FCO refuses to disclose the registered address of the legal entity that received the payments listed in its letter, on the basis that “release of the information could endanger the safety of individuals working for and with CIJA”, and stated that it does not hold the company numbers or legal jurisdictions of these organizations. It is thus not clear whether the FCO knew what entity it was paying.

Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (2012-2019)

As the ARK report described, US funding for CIJA was routed through another NGO named Syria Justice & Accountability Centre (SJAC). Its website states that SJAC was founded after a meeting of the Group of Friends of the Syrian People in 2012 and was based in The Hague for three years. This can be identified as Stichting SJAC (KvK number 59036699) formerly at Laan van Meerdervoort 70, 2517 AN, The Hague, but no longer registered. An article in Foreign Policy in 2014 reported that SJAC had been the conduit for US government funding of CIJA:

the commission’s grant was negotiated directly with the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. “The SJAC was effectively a bystander,” she said. “The money was channeled through SJAC to simplify our financial reporting, and to enable the SJAC to take credit, with our blessing, for [our] document collection.”

In 2016, SJAC closed down its operations in The Hague and registered (file number N00005464748) as a non-profit corporation in Washington DC hon 22 June 2016 by Mohammad Al Abdallah but its status is now listed as “Revoked” in the DC business register, perhaps because SJAC did not file the second report that would have been due on 1 April 2019. Mohammed Al Abdallah is listed on the SJAC website as Executive Director, having “previously worked as a research assistant for Human Rights Watch in Beirut from where he covered Syria”. He is the only governor listed on the business register. In May 2019 SJAC published a lengthy report based on material produced by CIJA.

SJAC, SCJA and CIJA are distinct from two other similarly-named NGOs:

- The Center for Justice and Accountability – registered in Washington DC (file number 980245) in 1998 with a business address in San Francisco.

- Syrian Institute for Justice & Accountability based in opposition-held Aleppo till late 2016 and reported by the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission to have provided witnesses for their investigations of alleged chemical attacks in 2017

Investigation by the European Anti-Fraud Office

The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) opened an inquiry into CIJA / Tsamota in May 2013 after receiving an anonymous complaint, though Tsamota did not become aware of this until March 2015. On 24 March 2020 OLAF announced in a press release headed “OLAF unravels fraud among partners in Rule of Law project in Syria” that

OLAF received information suggesting that a company based in the UK, and its partners in the Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates, might have been engaging in fraud against the EU budget, in relation to a “Rule of Law” project in Syria.

The “company based in the UK, and its partners in the Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates” correspond to Tsamota, CIJA and ARK. The press release continues with the statement that

OLAF established that the UK company, together with its partners, had entered into a contract with the EU to support possible prosecutions for violations of International Criminal and Humanitarian Law in Syria. The total value of this contract was EUR 1,999,830. OLAF’s investigation revealed that while the partnership claimed to be supporting the rule of law, the partners were actually committing widespread violations themselves, including submission of false documents, irregular invoicing, and profiteering.

In January 2020, the Director-General of OLAF closed the case, making judicial recommendations to the relevant national authorities in the countries where the partner’s offices were located, the UK, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Further recommendations were issued to the European Commission to recover EUR 1,896,734 and to consider flagging the partners in the Commission’s Early Detection and Exclusion System database.

The recommendation that the European Commission should recover €1.9 million of the €2 million originally awarded indicates that the OLAF investigators had concluded that most of the funding had been misappropriated. The “judicial recommendations” are understood to be recommendations for prosecution. Despite this, FCO spending records show that CIJA was still receiving funds from the FCO in May 2020.

A subsequent article by Arjen van der Ziel in the Dutch newspaper Trouw on 22 May 2020, together with a brief summary included comments from Wiley’s associates. Auto-translated extracts are given below:

The verdict, which the Belgian newspaper La Libre reported earlier this month, comes against the background of investigations that Olaf also conducted into suspected malpractice in investigating war crimes in Iraq’s neighbor Syria. In that project, a key role is played by the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), a non-governmental organization of which Wiley is also a director. According to Olaf, widespread irregularities were also found in that project. “While the project partners claimed to support the rule of law, in reality they violated rules on a massive scale, with false documents, irregular invoices and self-enrichment,” Olaf said in a recent press release. Wiley declines to answer questions about CIJA or the project in Syria. But Nerma Jelalic, one of his co-directors, assures us that the organization and its employees have done nothing wrong. She is furious about the investigation and calls the Olaf detectives a bunch of bums.

Trouw reported that OLAF’s investigation of Tsamota and CIJA, led by Daniel Iarossi, had begun in 2015 with a visit to CIJA headquarters.

But Nerma Jelalic, one of the directors of CIJA, assures that the foundation and its employees have done nothing wrong. She is furious about the investigation because, according to her, a noble initiative is unnecessarily dragged through the mud. “Even a war crimes suspect is treated better than how we were treated by Olaf,” said Jelalic.

Stephen Rapp was reported to have commented, after being briefed by Wiley, that “the accusations probably mainly concern the start-up phase of the initiative and mainly focus on ARK, the Dubai company of former diplomat Harris.” Harris’s business activities are outlined in an Appendix to this note.

Belgian court case: project “Higher Legal Education in Iraq”

In August 2012 the EU Directorate General International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO) had issued an invitation to tender for “a project to provide support to higher legal education in Iraq.” The contract for €1.834 million had been awarded in 2013 to Tsamota as head of a consortium with Gent University and two commercial companies. After a commisisioning an audit of the project, the EU informed Tsamota that payment of the final invoice had been suspended because “important information was missing, for instance the VAT number, company number and invoice number, and the invoice had been issued by a different entity, as had the last three invoices”. On 18 June 2018 Tsamota Limited brought a case in Belgium against the EU. The EU issued a counterclaim for recovery of funds already paid. The judgement was issued on 6 January 2020 and the case was reported in an article on 5 May 2020 in the Belgian newspaper La Libre. From the court judgement, some additional details of the OLAF investigation into Tsamota / CIJA are available.

Tsamota prevented OLAF from doing any on-the-spot control since no administrative office address of Tsamota where the original documents are stored has ever been communicated to OLAF.

Tsamota presented itself as leader of a consortium that never took place. Each of the other consortium members confirmed that they never signed a consortium agreement until late in the life of the project.

Tsamota has no stable structure and employs only consultants some of them with oral contracts. The whereabouts of the company’s administrative locations are difficult to follow.

Payments for security services were made to a bank account in Dubai and a bank account in Hong Kong and subcontracting for security service is in excess of what is allowed.

The short-term experts were recruited only from January 2015, towards the end of the project, when that should have been done from September 2013.

Services rendered by a key expert for the HLE contract have been charged twice for the same month … Accommodation for the experts has been charged twice.

OLAF literally and expressly doubts whether the project was actually implemented.

The court dismissed the claim by Tsamota, and ruled additionally that Tsamota must repay €378,855 plus legal costs. On this specific dispute, the court did not make a finding that fraud was proven although there were irregularities and poor record keeping amounting to “general administrative ‘nonchalance’”.

CIJA’s reaction to the story of the OLAF investigation

From a request based on the Government Information (Public Access) Act (Wob) some heavily redacted correspondence between CIJA and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs is publicly available. On 11 May the Ministry sought CIJA’s advice about how to respond to a Trouw journalist who had asked about the Dutch role in CIJA. CIJA responded with an eight-page letter to donors. Possible reconstructions of the redacted text are shown in square brackets.

There are two separate issues I want to address with you today:

- The claim –The claim – first put out by [Blumenthal and Norton] in outlets such as the [Grayzone site] (and now being picked up by newspapers in Belgium and the Netherlands) – that CIJA and [Tsamota] (a private company owned by [Wiley]) are one and the same.

- The claim that a press release put out by the EU’s OLAF on 24 March 2020 concerns an EU grant awarded to CIJA.

Although CIJA and Tsamota are not legally “one and the same”, as noted above they are co-located, have the same CEO and share key personnel. One of the irregularities identified by OLAF was that resources for CIJA had been diverted to Tsamota’s Higher Legal Education project in Iraq, allowing the contractors to make a profit from that project. More generally it is clear from the limited information that is available about the OLAF investigation that it concerned CIJA as well as Tsamota.

CIJA’s letter to donors continues with reference to an article “the objective of which is to discredit CIJA and [Tsamota]” published in June 2019; this is presumably the article by Blumenthal and Norton in the Grayzone. A subsequent heavily redacted passage may refer to the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media. Wiley had been aware since February 2020 that WGSPM members had been investigating possible irregularities in his business activities, originally as part of a broader study of the FCO-funding strategic communication programme related to the Syrian conflict. Possible reconstructions of redacted text are shown in square brackets:

Summer 2019: [The WGSPM, known for its questioning of the chemical attacks narrative] as well as for its attacks upon the reputations of the [White Helmets] and [James Le Mesurier] commences work on a “research paper” about CIJA, [ARK] and [Tsamota]. The same collection of [UK academics is] involved in putting together an alleged [?] – in which they attempt to link business and non-profit interests to a conspiracy in order to discredit the [White Helmets] – starts asking exactly the same questions about SCJA/CIJA as they did about [Mayday Rescue].

The WoB documents show a coordinated effort by the foreign ministries of several countries to keep the lid on the story of fraud, rather than to freeze all further funding pending the outcome of OLAF’s recommendations for prosecution. By 25 May CIJA was reporting that “only the [redacted] have managed to locate the OLAF file and review its contents”. A telecon with donors was held on 27 May. On 31 May CIJA thanked the Dutch Ministry of Foreign affairs for their “interventions at the donor meeting”.

It has been reported to us that the OLAF report led to a police investigation in Belgium, but this was abandoned because the UK authorities never replied to requests for assistance. The Trouw article reported in May 2020 that the Dutch Public Prosecution Service “confirms that the Olaf report is being studied to see whether there are leads for prosecution or other legal action.”, but there have been no reports of any subsequent action.

Collaboration of CIJA investigators with armed opposition groups

The work of CIJA’s “deployed in-country field team and trained investigators supporting documentation collection, exfiltration, archiving and analysis” was described in a report by Julian Borger in The Guardian in 2015, reviewed by Max Blumenthal and Ben Norton in 2015. Borger reported how “Adel”, described as the chief investigator for CIJA, had led a team that retrieved documents from eastern Syria in 2014 from territory controlled by opposition groups:

Adel had visited Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor in December 2013, with introductions from mutual acquaintances to a handful of the commanders of Islamist militias in the region.

In Raqqa, leaders of the local Salafist militia offered to help collect what Adel was looking for; over the next few days, they came to him with plastic bags and cardboard boxes full of papers from the abandoned secret police headquarters in the town of Taqba and from Raqqa city itself.

In Deir ez-Zor, the situation was more complicated. The dominant military force there was the Nusra Front, an al-Qaida offshoot opposed to any venture associated with the west. But one of the group’s local commanders – a man of “grace and education”, according to Adel – agreed to covertly provide assistance. His fighters allowed Adel’s investigators to comb through the military intelligence building and sweep up the files and loose papers scattered around its deserted shell.

It is not clear how CIJA came to have a “deployed in-country field team” that was so well-connected to rebel commanders affiliated to the Nusra Front in Deir-ez-Zor and to precursors of ISIS in Raqqa. An article in the Toronto Globe and Mail in 2019 gave a rather different account of how this collaboration with armed opposition groups was established:

Early in the war, Mr. Wiley struck a pact with the leadership of the Free Syrian Army, an anti-Assad umbrella movement that took over swathes of the country in 2011 and 2012

However even committed supporters of the armed opposition in Syria agree that the Free Syrian Army never had a cohesive command structure. CIJA’s collaboration with opposition groups on the ground might have been facilitated by US/UK operations to supply them with weapons. An article by Seymour Hersh in April 2014 described how a “rat line” was set up by the CIA and MI6 in Turkey in 2012:

The rat line, authorised in early 2012, was used to funnel weapons and ammunition from Libya via southern Turkey and across the Syrian border to the opposition. Many of those in Syria who ultimately received the weapons were jihadists, some of them affiliated with al-Qaida.

A highly classified annex to the report [of the Senate Intelligence Committee on the attack on the American consulate in Benghazi in September 2012], not made public, described a secret agreement reached in early 2012 between the Obama and Erdoğan administrations. It pertained to the rat line. By the terms of the agreement, funding came from Turkey, as well as Saudi Arabia and Qatar; the CIA, with the support of MI6, was responsible for getting arms from Gaddafi’s arsenals into Syria. … The involvement of MI6 enabled the CIA to evade the law by classifying the mission as a liaison operation.

Evidence supplied by CIJA in court cases

In July 2016 the Centre for Justice and Accountability filed suit against the Syrian Arab Republic for the murder of Marie Colvin, a journalist who had been killed in an artillery strike while embedded with the opposition in Homs. An expert report prepared by Ewan Brown was submitted as evidence in March 2018. In February 2019 two Syrians who had worked for the security service and defected in 2012 were arrested in Germany.

It was widely reported) that CIJA had provided the evidence that led to these arrests.

From reviewing the material submitted by CIJA in court cases it is possible to assess CIJA’s methodology and the evidence against the Syrian government that it has assembled.

The Central Crisis Management Cell documents

Brown’s report in the Colvin case summarizes a collection of documents known as the Assad files, obtained by CIJA from offices that were abandoned by the government during the Syrian conflict. From reports of the Koblenz trial, it appears that the testimony given by Christopher Engels representing CIJA also relied on these documents.

These documents, described as the “linchpin of the CIJA’s case against officials in the Syrian regime”, record the meetings and directives of the “Central Crisis Management Cell” (CCMC) established by the Syrian government in late March 2011 in response to the uprising that had begun a few weeks earlier. Section IB “Summary of Opinions” in Brown’s deposition outlines the case that he made based on these documents:

the security operations against opposition groups and individuals began immediately after the outbreak of demonstrations in February/March 2011 and escalated significantly as opposition activity spread (Section II and Section IV.A).

Regime security operations targeted those who participated in or supported demonstrations, opposition activists and those who organised, funded or disseminated materials to or had contact with media outlets (Section II and Section IV.A–B).

Regime operations resulted in mass arrests and detentions in security/intelligence run detention centres, the deaths of demonstrators, and the increasing use of the military in security

the Regime specifically targeted identified groups within the opposition. This included demonstrators, co-ordinators, funders and those who used the media to publicise activity within the country (Section II and III.A–B).

A key instruction in early August 2011 from the CCMC and disseminated by the NSB to governorate Security Committees directed that joint military/security operations were to be mounted against clearly identified groups (Section IV.B). This included those who were inciting demonstrations, financiers of demonstrations, members of opposition coordination committees and those who communicated with people abroad in order publicise demonstrations or ‘tarnish the image’ of Syria in the foreign media and within international organisations.

Many [of these identified groups] were detained for prolonged periods and were subjected to intimidation, physical violence, and torture, which at times resulted in death.

Brown’s deposition asserts that the Syrian security forces undertook mass arrests and detentions of protesters” immediately after the outbreak of demonstrations in February/March 2011″ and that the armed opposition emerged only in late summer 2011, after “security operations targeted those who participated in or supported demonstrations”.

As the summer developed [in 2011], the security situation continued to deteriorate. The increasingly violent response of the Regime inflamed the opposition, leading to additional protests and the emergence of an armed opposition.

Other accounts record however that ambushes of Syrian soldiers began at the end of March 2011, with 88 Syrian soldiers killed during April 2011 in separate attacks across Syria, even before the army had been deployed for internal security duties. The Syrian government did not report these casualties at the time, perhaps in the belief that publicity would help its adversaries. By 8 May 2011, the CCMC was requesting daily reports on casualties among “our own forces”:

You are requested to provide us with a daily written report for the period up to 18:00. The report shall include: 1. Our own forces – Position – Situation – Actions carried out – Losses in detail – Wounded – Martyred – Equipment

2. Hostile forces – Demonstrations and where they took place – Acts of rioting and sabotage – Shooting at our own forces – Killed – Wounded – Detained

An instruction issued on 12 March emphasized that citizens should not be provoked, and that security forces should “comply with the instructions issued by the National Security Bureau concerning the summoning and detention of citizens”:

In order to avoid the consequences of continued incitement, such as the call for organising the Day of Wrath on 4 and 5 February, and foil the attempts of inciters to exploit any pretext, civil police and security agents are requested not to provoke citizens. … it is necessary to study the sociological effects of any security related incident which involves citizens, who should not be provoked. And all security apparatuses and civil and military police should comply with the instructions issued by the National Security Bureau concerning the summoning and detention of citizens, as these instruction are aimed at preserving the integrity of security work whose objective is to achieve the stability and security of the country.

An instruction dated 6 April 2011 referred to recent events in which these demonstrations led to attacks on buildings and people.

You are requested, each in your work area, to call the security committee to convene to discuss the latest developments, particularly the calls for demonstrations, and organize marches in all districts given the information regarding the intentions of some opponent groups to carry out acts of sabotage—burning of political party offices and assaulting party comrades and security personnel… as happened to police members in Rural Damascus.

On 20 April:

Detailed plans should be developed to counter the possibilities of armed and unarmed demonstrations and sit-ins,

On 11 May the CCMC quoted a leaflet issued by the opposition which outlined a plan for using demonstrations to divert and exhaust security forces and to provoke foreign intervention as in Libya:

Therefore, if there were demonstrations in Damascus, Dar’a and As- Sweida, security forces will lose control of all regions. This is because they will be exhausted and distracted, and they will not be able to target a specific city, and their strikes will be lighter and less intense against the residents of all of these provinces together. This also applies to all regions as the regime will be confused and will not be able to bring enough forces to cover a specific region as its forces will be engaged with other regions. Besides, the continued state of high alert will quickly exhaust security forces because they will be taken unawares and will not be able to draw a security plan that covers all regions, which will make toppling down the regime [incomplete sentence] with the many convictions, and the decision of the Security Council to conduct a military strike against Qaddafi.

By June 2011 the weekly incident reports include mention of the abduction and torture of government supporters, and by November 2011 the security forces report finding bodies of unidentified victims:

A refrigerated vehicle was found on the Homs-Zaydal highway, containing (27) unidentified bodies displaying gunshot wounds and signs of torture.

By 23 August the Ministry of Security was requesting information on thse who had contact with foreign bodies that “took part in funding and arming demonstrators”. This implies that by this time the “demonstrators” were armed.

You are kindly requested to supply us with the information that has been available from your interrogation of detainees who incited demonstrations and those who had contacts with foreign bodies, whether they are media bodies or plotters, or bodies which took part in funding and arming demonstrators

The documents emphasize the necessity of avoiding bloodshed when dealing with peaceful protests. On 20 April 2011:

Counter with weapons those who carry weapons against the state, while ensuring that civilians are not harmed.

At a meeting on 24 April, the government appeared to blame security forces for failing to follow these directives on 22 April, when “rights groups” reported that protesters in Daraa and Douma had been shot by security forces:

Comrade Assistant Regional Secretary spoke, stating that 22/4/2011 was a difficult day in which several people died which created a new situation in the country, pushing us into circumstances we are better off without. If the directives previously issued had been adhered to we would have prevented bloodshed, and matters would not have come to this culmination.

The discussion alluded to the role of opposition snipers in shooting from roofs or “through” demonstrations, presumably to provoke security forces into opening fire.

Comrade Director of the General Intelligence Directorate expressed his willingness to present the images of those shooting from the roofs of houses or through demonstrations or ambushes, and to provide the appropriate evidence. Comrade Assistant Regional Secretary stated that surrounding and catching a sniper alive or injured and exposing him in the media is not impossible. This mission should be accomplished.

An Instruction dated 15 August 2011 specifies that police and anti-riot personnel must wear uniforms and must:

4 – Ensure that no drop of blood is shed when confronting and dispersing peaceful demonstrations.

A set of instructions issued on 9 November included an order to “prohibit harming any detainee”.

This comparison of Ewan Brown’s written evidence in 2018 with the original documents supports an earlier analysis based only on extracts from these documents, which argued that CIJA has distorted the original documents which record the Syrian government’s response to an armed insurgency to make it appear that the Syrian government was responding to peaceful protests with mass arrests and with militarization of the uprising. There is no evidence in these documents that maltreatment of detainees was sanctioned by the Syrian government. Again we emphasize that we take no position on whether such maltreatment occurred, only on whether these documents provide evidence for it.

The Caesar photos

As noted above, CIJA worked on the Caesar photos with Toby Cadman from 2015, and Fergal Gaynor’s CV records that he also worked on them as head of the Syrian Regime Team from 2017 to 2019. Although the Caesar photos formed part of the prosecution’s case in the Koblenz trial, it is not clear whether CIJA was involved in providing evidence.

The individual using the codename “Caesar” was first presented on 20 January 2014 as the source of an archive of photographs of thousands of deceased adult males taken over an eight-month period up to August 2013 at the mortuary of Military Hospital 601 (Martyr Youssef Al-Adhma Hospital) in Damascus. In July 2014, Caesar accompanied by his handler Mouaz Moustafa, a former Senate staffer gave a presentation to the Foreign Affairs Committee of the US House of Representatives.

On December 20, 2019, the annual U.S. National Defense Authorization Act passed and became law. Included in that legislation was the “Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act,” an act named after Caesar. The act targets the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his allies, including Russia, Iran, the militant group Hezbollah, and those that support his regime, with economic sanctions.

Human Rights Watch, who were given access to the entire archive, reported in December 2015 that nearly half of the images were of government soldiers killed in action. The remaining images show at least 6000 adult males, many of whom had signs of starvation, other maltreatment, or mutilated bodies. These bodies were labelled with numbers.

In the original report released by Carter-Ruck and partners in January 2014, Caesar testified that he had been employed as a photographer at Hospital 601, and that most of the deceased were civilians detained and killed by Syrian security forces. At this stage Caesar did not mention that detainees had been held in the hospital itself, only that their bodies had been taken to the hospital “so as to document, falsely, that death had occurred in the hospital”.

Another witness testified that he was Caesar’s relative by marriage and that Caesar had been working with him since 2011. The identity of this individual was reported elsewhere to be Hassan al-Chalabi, secretary-general of the Syrian National Movement. Human Rights Watch reported in December 2015 that “Members of that group formed the Syrian Association for Missing and Conscience Detainees (SAFMCD), which took custody of the files.” The domain name safmcd.com was registered on 25 January 2015. The Syrian National movement (originally named the Islamic Current is an opposition group founded by the Islamic scholar Emad al-Din al-Rashid who was interviewed by the New York Times in Istanbul in 2012. From its posts on Facebook, the position of this group appears to be close to that of the Turkish government.

A report released by the Syrian Network for Human Rights in October 2015, including additional testimony from Caesar alleged that from 2011 onwards the Trauma Department of Hospital 601 had been transformed into a detention centre. By April 2017 another purported eyewitness reported that the hospital itself was a torture centre.

The Syrian government issued a statement that the photographs were of unidentified persons including foreign opposition fighters killed in the conflict and civilians who had been tortured and killed by the opposition, but provided no evidence to support this explanation. Several lines of evidence however cast doubt on Caesar’s story and support the Syrian government’s explanation:

- Caesar’s testimony in 2015 that part of Hospital 601 was used as a detention centre was not mentioned in the 2014 report of his testimony.

- The OPCW Fact-Finding Mission Team B led by Steven Wallis that investigated alleged chemical attacks on Syrian soldiers, visited Hospital 601 on 27 May 2015 and on 13 August 2015. The inspectors were given a tour of the facilities, were allowed to study the hospital’s record keeping systems and were allowed to select medical staff for interview. Their report noted that “Hospital 601 is operating under crisis conditions” but did not indicate that any part of the hospital was used to hold detainees.

- Transfer of bodies to the morgue of a hospital to be photographed with numbered labels is consistent with the Syrian government’s statement that the victims were unidentified. If the victims had been civilians detained by security forces and killed within the prison system, security forces would have known their identities and there would have been no need to photograph them with numbered labels. Caesar’s explanation that the bodies were brought to Hospital 601 so that death certificates could be falsified is convoluted: falsifying death certificates would not have required transfer of the bodies.

- None of the victims were wearing prison uniforms: their bodies were mostly naked, in underwear, or in street clothes.

- The 2015 report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights noted “the presence of insects and dried wastes that appear to be bird wastes, in the victims’ eye sockets and mouths”, indicating that the bodies had been abandoned for some time in the open. This observation is more consistent with killing by the opposition (followed by dumping the bodies) than with killing within the state prison system.

- Some victims had evidently died while receiving intensive medical care, with cardiac monitoring electrodes, central venous catheters and in one case an endotracheal tube still in place. As, the German forensic specialist who testified in the Koblenz trial noted, where electrodes were visible they were placed correctly for cardiac monitoring. This suggests that the hospital attempted to save those victims who reached the hospital alive, and allocated scarce intensive care resources for this.

- In a few victims, tattoos indicating Christian or Shi’a Muslim religious affiliation were present. These groups were unlikely to have supported the armed opposition.

As Tim Hayward noted in April 2019, UK-based communicators who have promoted the narrative of chemical attacks in Syria have not promoted Caesar’s story. One possible explanation for this is the confrontation between Qatar, the initial sponsor of the story, and its Arab neighbours. More recently, a sceptical article by Max Blumenthal in June 2020, asserting that the Caesar affair was “a US and Qatari regime change deception” was mirrored` without comment on the website of the Syrian Observatory of Human Rights, a UK-based outlet that has received FCO funding.

We emphasize that we do not know which side was responsible for starving and killing these victims: we note only that evidence casts serious doubt on “Caesar’s” story that the victims were detainees of the Syrian state.

Reports of the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry

Brown’s deposition cited uncritically the reports of the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry (CoI) on the Syrian Arab Republic. For instance this account of the fighting in Homs in early 2012 was quoted without any supporting evidence that security forces committed these crimes.

Several areas were bombarded and then stormed by State forces, which arrested, tortured and summarily executed suspected defectors and opposition activists.

Brown quoted the CoI’s account of a massacre of civilians in March 2012 without mentioning that the attribution for this massacre is disputed:

On 11 and 12 March 2012, the neighbourhood of Karm al-Zeytoun reportedly came under an attack by what was described as Shabbiha protected by the army. Multiple families were killed in their homes, apparently by knives or other sharp instruments. Estimates of casualties, unverified by the commission, ranged from 35 to 80 in that attack.

This massacre, and others in the Homs region at around that time, was reported in Syrian state media at the time and attributed to the opposition. The CoI’s report on this and other incidents relied entirely on anonymous opposition sources, and should not have been cited as evidence in a legal process.